Langkawi, Taman Geo Global Pertama Di Asia Tenggara

Dataran Lang yang terletak di Persiaran Putera Kuah, Langkawi. Foto Facebook Jalan Jalan Langkawi

KUALA LUMPUR, 23 OKT: Geopark atau taman geo adalah tapak warisan yang menampilkan aspek sejarah dan geografi yang boleh dimanfaatkan oleh semua pihak bagi tujuan pembangunan, pendidikan dan pemuliharaan lestari.

Di Malaysia, terdapat beberapa tapak yang diisytiharkan kerajaan sebagai geopark, namun hanya dua bertaraf global, iaitu diiktiraf oleh Pertubuhan Pendidikan, Kebudayaan dan Saintifik Pertubuhan Bangsa-Bangsa Bersatu (Unesco) setakat ini – Langkawi yang menerima status itu pada 2007, dan terbaharu pada Mei 2023, Kinabalu Geopark.

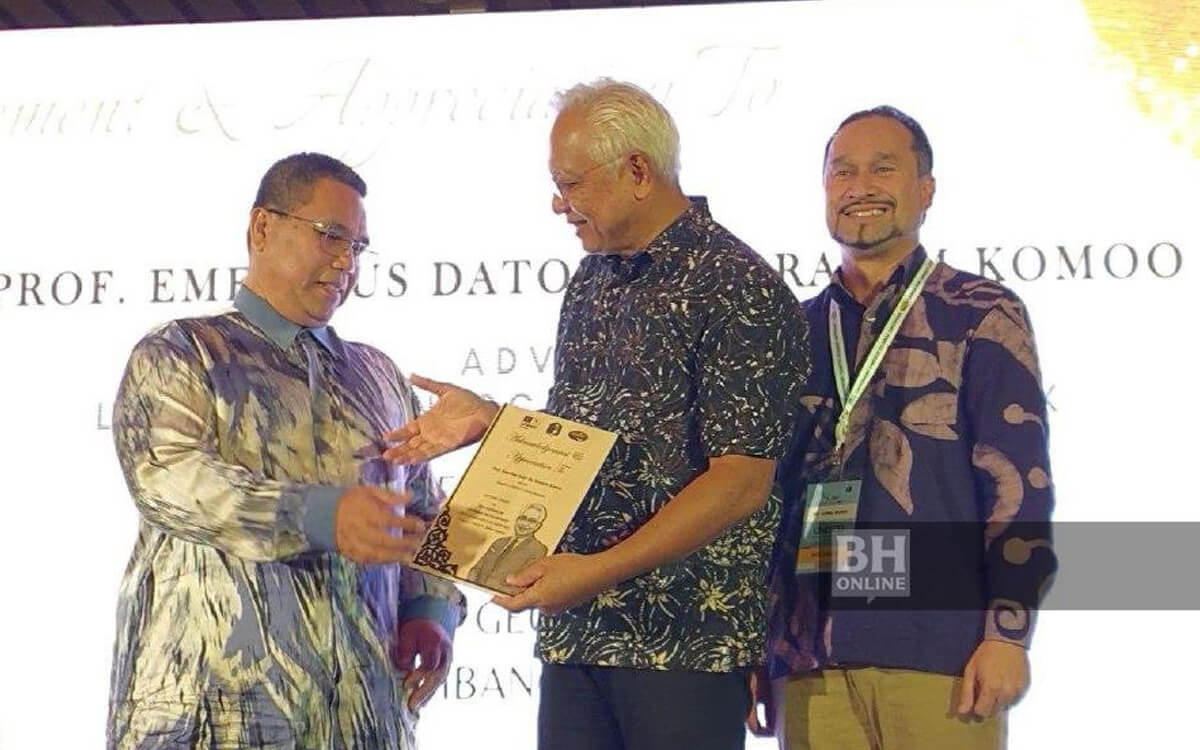

Menurut Penasihat Langkawi Unesco Global Geopark Prof Emeritus Dr Ibrahim Komoo, bukan mudah untuk memperoleh status itu dan cabaran seterusnya ialah mempertahankan penarafan tersebut.

Langkawi yang juga geopark global pertama Asia Tenggara, menampilkan keunikan menerusi himpunan 99 buah pulau dan ini turut menjadi cabaran kepada pentadbir, iaitu kerajaan Kedah dan Lembaga Pembangunan Langkawi (Lada) dalam mengekalkan status geopark global Unesco hingga ke hari ini.

Ibrahim berkata pelbagai usaha dilaksana bagi memastikan taman itu dapat mempertahankan status kad hijau buat kali keempat berturut-turut sejak 2007.

“Kad hijau adalah pembaharuan label Unesco Global Geopark. Sejak menerima status itu, kita berusaha tanpa mengenal lelah untuk memastikan kita dapat mengekalkan status geopark global, dan status ini berjaya dipertahankan sekali lagi pada awal September lalu,” katanya dalam temu bual dengan Bernama baru-baru ini.

Ujarnya, pencapaian itu adalah sesuatu yang harus dibanggakan oleh seluruh negara kerana tidak mudah untuk memenuhi kriteria yang disyaratkan di bawah Unesco Global Geopark.

Pemandangan Tasik Dayang Bunting. Foto Facebook NF Vibrant Holidays Sdn Bhd

Serampang dua mata

Ibrahim yang juga Felow Utama Institut Alam Sekitar dan Pembangunan, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, berkata pembabitan pelbagai pihak diperlukan dalam mempertahankan status itu.

“Contohnya, semasa penilaian ketiga pada 2019, antara yang kami ketengahkan kepada penilai Unesco ialah penyertaan pengusaha hotel yang mewujudkan galeri geopark di hotel masing-masing, sekali gus mencerminkan kefahaman mereka tentang perlunya pembangunan geopark ini dilakukan secara bersama-sama.

“Kemudian, semasa penilaian terbaharu pada tahun ini, kami mewujudkan dua produk berkaitan pelancongan geo. Satu daripadanya ialah mengubah Gunung Raya menjadi kawasan taman hutan geo baharu. Kawasan ini merangkumi Kilim Karst, Machinchang dan Tasik Dayang Bunting.

“Selain itu, kita juga berjaya mewujudkan lima denai geo baharu sebagai tambahan kepada Kubang Badak BioGeo Trail,” jelas beliau.

Satu daripada denai baharu tersebut ialah di Pulau Tuba, dan menurut Ibrahim, laluan itu dibangunkan sejak dua tahun lalu susulan penemuan penyelidikan bahawa terdapat 28 tapak yang mempunyai nilai geologi, biologi dan warisan kebudayaan di pulau berkenaan.

“Menerusi penyelidikan ini, Lada membangunkan beberapa denai yang menghubungkan kesemua 28 tapak dengan bantuan penduduk setempat. Pemandu pelancong akan memberi pencerahan tentang kesemua lokasi ini sambil pelancong melewati tempat-tempat berkenaan.

“Penduduk juga telah menubuhkan Persatuan Best Tuba yang bagi saya agak menarik kerana mereka terlibat secara aktif dalam projek denai geo ini. Mereka juga bersedia menawarkan pelbagai jenis pengangkutan seperti bugi elektrik bagi memudahkan pelancong menyelusuri denai,” katanya, menambah projek turut bertujuan meningkatkan lagi sosioekonomi penduduk setempat.

Kereta kabel Langkawi terletak di Gunung Mat Chinchang, barat laut pulau Langkawi. Foto Facebook Nik Nurfarahin Abdullah

Kerjasama semua pihak

Bercerita lanjut, Ibrahim berkata Langkawi Unesco Global Geopark mempunyai biodiversiti yang luas meliputi paya bakau, pantai dan muara sungai, sekali gus membuatkan kawasan itu begitu bernilai dan perlu dilindungi tanpa kompromi.

Taman geo ini mempunyai jujukan sedimen atau mendapan era Palaeozik paling terdedah dan lengkap di Malaysia, iaitu dari tempoh Kambrium hingga Permian yang berlaku sekitar 220 juta tahun dahulu.

Mujurlah katanya usaha menjaga dan memulihara warisan alam itu mendapat sokongan penduduk setempat yang bukan sahaja menyediakan pelbagai kemudahan untuk pelancong tetapi turut memastikan kemudahan tersebut seiring usaha memulihara.

“Pendek kata setiap orang memainkan peranan mereka. Begitu juga institusi pendidikan seperti sekolah yang bekerjasama dengan kita. Ada 32 sekolah yang mewujudkan sudut maklumat taman geo di sekolah masing-masing, selain penyertaan pelajar dalam program kita, menunjukkan minat mendalam generasi lebih muda dalam melindungi permata alam semula jadi ini,” katanya.

Menjaga alam semula jadi

Sementara itu, Pengurus Pelancongan Lada Dr Azmil Munif Mohd Bukhari berkata agensi tersebut sentiasa bekerjasama dengan pelbagai pihak termasuk Jabatan Geosains dan Mineral dalam menangani impak perubahan iklim terhadap alam sekitar di Langkawi Geopark.

“Kami membangunkan sistem amaran awal yang ditempatkan di lokasi-lokasi strategik terutama di air terjun Telaga Tujuh, di mana di situ adalah laluan mendaki ke Gunung Machinchang.

“Sistem amaran awal ini akan memaklumkan jika hujan lebat melanda dan kemungkinan berlaku kepala air serta angin kuat yang boleh membahayakan pelancong di kawasan itu,” katanya.

Bagi melindungi nilai warisan alam semula jadi, Lada memastikan tidak ada sebarang pembangunan tidak perlu dilaksanakan di hutan simpan kekal di Langkawi.

“Kita bertuah kerana hampir 60 peratus kawasan geopark di Langkawi ini terletak di hutan simpan kekal yang dilindungi sepenuhnya oleh Akta Hutan Perhutanan Negara 1984.

“Sehubungan itu, kami mengehadkan pembangunan kepada seminimum mungkin, iaitu hanya sekadar memenuhi keperluan pelancong dan penduduk setempat, antaranya jeti, kawasan letak kenderaan, gerai serta pusat penerangan. Pembangunan tidak boleh dilakukan sewenang-wenangnya bagi melindungi lokasi warisan alam semula jadi ini,” jelas beliau.

-BERNAMA

The article was originally published at

https://selangorkini.my/2023/10/langkawi-taman-geo-global-pertama-di-asia-tenggara/